I have had to give up on this book by Jonathan Black.

Giving up on books (and movies, for that matter) is not something I do lightly. I'll generally soldier through no matter how heavy the going gets, partly because of pride and partly out of a misplaced belief that it must get better than this, mustn't it? With this one, though, I've lost interest to such a degree that even my over-weening pride can't carry me through. It's doubly difficult because this was a Christmas present from my wife. In these cases one is obliged to clear one's plate and end the meal with a smile, but on this occasion I wasn't able.

This one came from

PostScript. PostScript is a rather nifty mail-order clearing house specialising in remaindered academic and specialist books. We've been customers for a long time and I've gotten some really fabulous books from them over the years. That slightly interesting academic books you saw reviewed in Fortean Times becomes a whole lot more attractive when the RRP of £24.99 is reduced to £4.99!

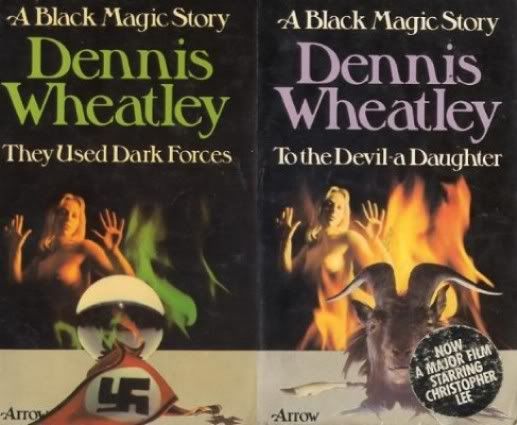

It was listed as a trawl through the history esoteric thought, which, as I noted in my review of the year, is a subject that I find intriguing. I used to devour this studff as a kid: Peter Haining "true mysteries" books, Arthur C Clarke's Mysterious World, Chariots of the Gods and Unexplained magazines. In my twenties I discovered Colin Wilson's books on the topics, which were the same sort of thing for grown ups, and of course the wonderful Fortean Times.

I'm not a believer, although I suppose I maintain a healthy Fortean scepticism on scientism, and as an artsy fartsy type I'm inclined to believe that there's more to life than flesh and dirt. I think, though, that I enjoy this stufdf as a kind of REAL sci fi or REAL fantasy. UFOs generate the same kind of sensawunda that SF does, and poltergeist reports create the same frisson of the uncanny as MR James. It all comes form the same place, I think, but when you start believing it... well, next stop Scientology, I suppose.

Which brings us to this volume. It's a very handsomely produced hardback, with thickl creamy paper and packed with interesting illustrations, inlcuding two sets of slick, colour reproductions of various bits and pieces. It's from Quercus, a major non-fiction publisher, and so one would hope the content would match these high production values. It doesn't, though, not by a long shot!

It is, essentially, a detailed overview of the kind of devolutionary theory that's familiar from theosophy. Humanity starts as pure spirit, and slowly degrades through various stages of corporeality to rude matter; and the purpose if life is to pierce the veil of maia and return to the spiritual thingamabob. This is described through one of those great esoteric crawls through history where anything cross-shaped is a crucifix, every flood myth is a memory of Atlantis and every archway is a wink from the freemasons.

I have a high tolerance for bullshit (obviously, otherwise I'd have poisoned myself by now) but the problem with this book is the flaccid vacuity of it all. Mr Black makes a great deal of assertions that are not backed by references to original sources or really discussed in any detail at all. I usually come to a book like this looking for the author to winkle out shades of meaning or detail and cast new light - however incorrectly - onto various bits of myth or history, but this guy does none of that.

The "classic" volumes of this sort for me are the

Colin Wilson books The Occult and Strange Powers. Colin's obviously a trifle deranged, but he examines his subjects in great depth and argues for his conclusions quite forcefully (if memory serves, a mix of Gurdjieffian and Crowleyian occultism-as-mind-focusing that produces psychis experiences). There's none of that here. It's more of a man-in-the-pub ramble where the history and evidence is made to fit the preconceived notions of the author.

Sigh, such a shame! I really love these types of book, but I am, perhaps, now too well read in this subject for this particular strain of book to hold much new information for me. Certainly when I see the same old well-debunked names popping up (Graham Hancock, Robert Temple, David Rohl) my eyes begin to glaze over. Better are the recent works of Gary Lachman based on original research and often new interviews Those In The Know, the work of Erik Davis (such as the superb Techgnosis) or, as recommended in my round up of 2009, Madame Blavatsky's Baboon by Peter Washington. These authors manage to illuminate the history of esoteric thinking in level-headed yet skepticism light way that eludes Black here.

There's a couple of other odd things about this book, both pointed out by Hilary Mantel in her

funny review that appeared in the Guardian in 2007. First off, it's hard to avoid the suspicion that this is just a cash in on the Da Vinci Code. Black name checks Dan Brown in the first few pages and the facts-light tone of the thing and welath of illustrations hints at a rush-job by a publishing insider with a whiff of easy money in their nostrils.

The other puzzle about this book, is that Jonathan Black is pen name for Mark Booth, former head of the Century imprint at Random House who has recently (google reveals!) moved to Hodder & Stoughton. Mantel says: "Here's an age-old mystery before we start: why do authors do that? Surely you must either assume a false identity, or publish under your own name; how can you do both?"

How indeed!